-

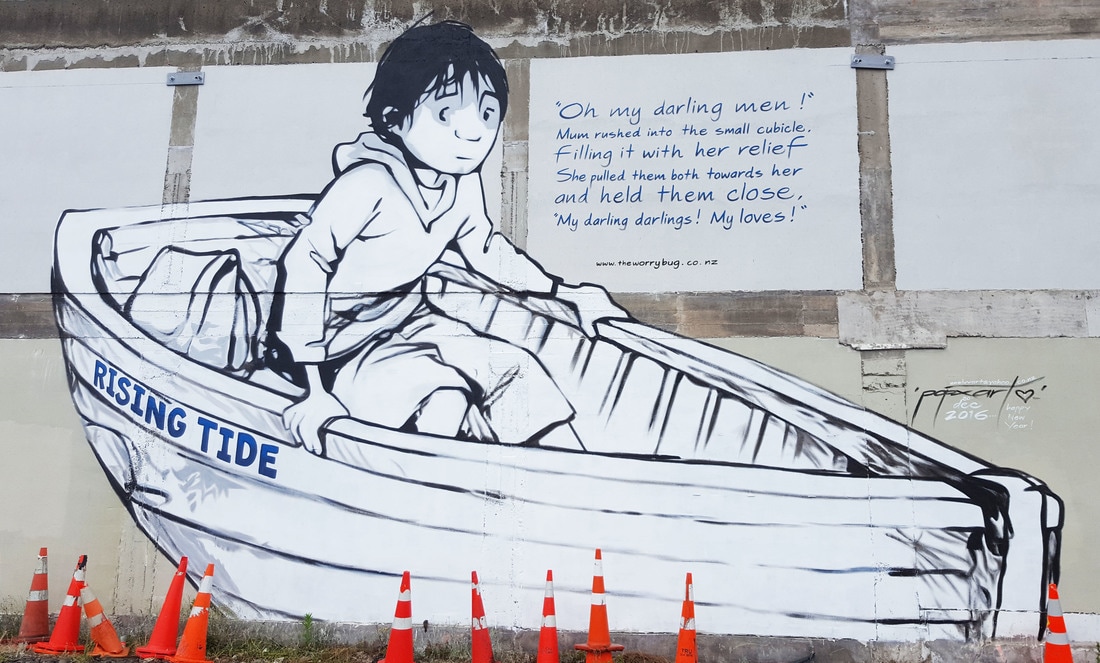

Rising Tide Lesson Plans

-

Best Practice

-

Extra Support

-

Massey University Research Invitation

<

>

|

Dear SENCos, teachers, support staff and homeschooling parents

The following suggested learning activities have been designed for students in years 5 to 8. Children in this age group are moving towards independence and are continuing to develop skills in making decisions as they become more independent. They are beginning to look to peers and media for information and advice. They are also developing an increased capability for social conscience and for abstract thought, including understanding complex issues such as poverty, war and natural disasters. The suggested activities are designed to be worked through from beginning to end, or for you to adapt, add or omit activities to fit the needs, abilities and year level of your class. The activities help to develop a supportive classroom culture and can be used in the last 20–30 minutes of each day, or in larger blocks. It may be that you have a group of students who need extra support prior to attempting these activities. For this group we recommend using or adapting the activities in Wishes and Worries (Sarina Dickson, 2014). We have used the concept of Home and School Scaffolding at the heart of this resource. Home and School Scaffolding utilises the trusted attachment relationships children have within their homes and schools to support them to develop their emotional intelligence. The activities for classrooms and homes have been informed by evidence-based Cognitive Behaviour Therapy and Narrative Therapy, and by the objectives of the New Zealand Curriculum. For more information about the evidence-based research behind the resource please see our website. We’d love to receive any feedback about how you used 'Rising Tide' and the suggested activities. Warmest regards Sarina Dickson and Julie Burgess-Manning |

Watch this short clip of Registered Psychologist and co-author of

Rising Tide, Julie Burgess-Manning, to gain a greater understanding of ways to increase the effectiveness of Rising Tide in your classrooms. |

|

When the Worry bug books came out, schools used them in a myriad of different ways. We wanted that, and in fact thought that it would work better if schools decided how they would use them, rather than being told how to suck eggs. But, from that implementation, Massey did some research on their use in all the schools in Christchurch and found some interesting things.

Firstly, those schools that were more prepared for their use seemed to notice more impact in their communities. These are some suggestions drawn from your ideas from that research. |

Watch this short clip to see how Heathcote Valley School used Rising Tide.

|

-Appoint someone to drive the project, and ensure they are supported in that role by senior leadership.

-Plan together as a teacher group, how and when you will use the resource, so that the resource is being worked with simultaneously across the school, enabling conversations around it to occur more spontaneously. Do lead-in, process and reflective planning especially to prepare yourselves as teachers for unexpected responses from children.

-Use the exercises provided for teachers to develop your teaching plan.

-Use the exercises daily for a couple of weeks as you read the book, integrating it across the curriculum as a literacy activity, for art, for health, creates more of an impact as it occurs across multiple learning areas.

-Reviewing the book frequently, engaging with key phrases or learning points will mean the growth of a new culture or well- being, and may encourage teachers and students to access other ideas for well-being also.

Plan how you will inform parents, then share the project with parents at an early stage and continue to discuss it in your conversations with them and within interviews, mention it in newsletters.

Changing Classroom Culture

A change in coping style for children is complex, but do-able. It is one thing to teach techniques or tools that will help children manage their responses and build resiliency, but what works better is to create a change in belief or coping style. This is best done by using thoughtful and methodical approaches, planning well, incorporating review and reflection, on-going use of language and resources in order to embed the new style. A critical part of this kind of change is that adults around the children are role-modelling the new style and supporting the child’s use of it multi-situationally. So, when you come across a disagreement in the playground, a child feeling put down, another feeling ashamed, you manage this using the very tools you are teaching. Children are encouraged to express and to empathise in this book, you too will need to empathise and be authentic in your response to both parties. Engage with the thoughtful, brave, resilient parts of yourself and you will encourage children to use these parts of themselves, to rise above the ‘names’ they have called themselves, and investigate new ones.

We welcome feedback around the ways your school has used 'Rising Tide', and please consider being part of the next stage of Massey University's research.

Here are some specific suggestions from schools that used The Worry Bug resources:

-Plan together as a teacher group, how and when you will use the resource, so that the resource is being worked with simultaneously across the school, enabling conversations around it to occur more spontaneously. Do lead-in, process and reflective planning especially to prepare yourselves as teachers for unexpected responses from children.

-Use the exercises provided for teachers to develop your teaching plan.

-Use the exercises daily for a couple of weeks as you read the book, integrating it across the curriculum as a literacy activity, for art, for health, creates more of an impact as it occurs across multiple learning areas.

-Reviewing the book frequently, engaging with key phrases or learning points will mean the growth of a new culture or well- being, and may encourage teachers and students to access other ideas for well-being also.

Plan how you will inform parents, then share the project with parents at an early stage and continue to discuss it in your conversations with them and within interviews, mention it in newsletters.

Changing Classroom Culture

A change in coping style for children is complex, but do-able. It is one thing to teach techniques or tools that will help children manage their responses and build resiliency, but what works better is to create a change in belief or coping style. This is best done by using thoughtful and methodical approaches, planning well, incorporating review and reflection, on-going use of language and resources in order to embed the new style. A critical part of this kind of change is that adults around the children are role-modelling the new style and supporting the child’s use of it multi-situationally. So, when you come across a disagreement in the playground, a child feeling put down, another feeling ashamed, you manage this using the very tools you are teaching. Children are encouraged to express and to empathise in this book, you too will need to empathise and be authentic in your response to both parties. Engage with the thoughtful, brave, resilient parts of yourself and you will encourage children to use these parts of themselves, to rise above the ‘names’ they have called themselves, and investigate new ones.

We welcome feedback around the ways your school has used 'Rising Tide', and please consider being part of the next stage of Massey University's research.

Here are some specific suggestions from schools that used The Worry Bug resources:

- Initially used in school assembly on screen with a reading, with continuing follow-up in classrooms

- Used in reading group

- Used in circle time discussion

- Used in classroom story time as follow-up to disaster drills

- Used in writing poetry

- Used in art class

- Used in social science/health class

- Posted photocopies of illustrations in classrooms as part of continuing awareness

- Brief display of classroom poster with children’s worries on classroom wall

- Planned repeat use in coming year

- Sent home story book with youngest rather than eldest of a family’s children

- Set up of a letter box for posting worries as an ongoing follow-up for children to receive school support following school story book use

- Placed Worry Bug updates in the school newsletter

- Placed both school and home story in school library for ready access to children

- Discussion with parents who viewed Worry Bug art productions by their children

Magical thinking, mind reading, catastrophising, dominant vs subjugated stories and avoidance

The ideas below, with the supporting videos, may help in understanding some of the psychological issues that come up when you are working with your children. It is important that, when you consider the ideas, you realise that children do not work as individuals, but in a system – that is, as part of a system with their family or their friends and their class. We cannot expect children to change by themselves. They need help to understand their worries and to understand how they might change. Then, they need adults to guide the change and help them to be consistent with it. Further, they often need the adults in their lives to change as well. Some of these ideas may apply equally to you as to your children.

Magical thinking and Mind reading

Many children believe in things that we as adults would not. For instance, if there is a noise from under the bed at night, children are more likely to think that there is a monster there. Or they might think that, because something bad happened last time they did a particular thing, they shouldn’t do that thing again. We call this ‘magical thinking’. The term covers a multitude of things and of course adults do it too, for instance, avoiding walking under ladders, or counting up to 10 and expecting a parking space to become free.

Ari worries that his teacher can read his mind and see all his secrets. He avoids meeting her gaze and has to change his behaviour so that she doesn’t challenge him. He has a belief that she can see into his mind and know his thoughts. As children learn empathy and develop an ability to distinguish themselves as separate to others, they are more able to resist this mind-reading mistake.

The ideas below, with the supporting videos, may help in understanding some of the psychological issues that come up when you are working with your children. It is important that, when you consider the ideas, you realise that children do not work as individuals, but in a system – that is, as part of a system with their family or their friends and their class. We cannot expect children to change by themselves. They need help to understand their worries and to understand how they might change. Then, they need adults to guide the change and help them to be consistent with it. Further, they often need the adults in their lives to change as well. Some of these ideas may apply equally to you as to your children.

Magical thinking and Mind reading

Many children believe in things that we as adults would not. For instance, if there is a noise from under the bed at night, children are more likely to think that there is a monster there. Or they might think that, because something bad happened last time they did a particular thing, they shouldn’t do that thing again. We call this ‘magical thinking’. The term covers a multitude of things and of course adults do it too, for instance, avoiding walking under ladders, or counting up to 10 and expecting a parking space to become free.

Ari worries that his teacher can read his mind and see all his secrets. He avoids meeting her gaze and has to change his behaviour so that she doesn’t challenge him. He has a belief that she can see into his mind and know his thoughts. As children learn empathy and develop an ability to distinguish themselves as separate to others, they are more able to resist this mind-reading mistake.

Catastrophising

When we have any kind of thought, we can respond to it in different ways. For example, you might be thinking about going to a wildlife park on your birthday with your best friend. You feel excited about this because you want to get to the lion cage and see those big cats close up. But your friend says that he is afraid to come because the lion might reach through the cage and get him. These are two different responses to the same situation. One of them is an example of catastrophising.

Ari makes a catastrophe out of not being able to spell “Theodore Street”. It links to his belief that his trouble with reading, writing and spelling means that he is stupid and he makes this an even bigger catastrophe by thinking his family will be angry about it. That means he can’t talk to anyone he trusts about his problems, and he has to find ways to hide them. This in turn leads to the situation with the boat, and nearly drowning: a real catastrophe.

Managing catastrophising requires a calm head. Using clear, logical thinking is one way. Testing the logic of thoughts by comparing them to other people’s experiences can be helpful. For instance: “Has anyone else I know ever been bitten by a lion at that park? What kind of precautions do they take to stop the lions getting people?” Or: “Do other people have trouble with spelling? Do my parents often get angry with me when I am having trouble with something?”

When we have any kind of thought, we can respond to it in different ways. For example, you might be thinking about going to a wildlife park on your birthday with your best friend. You feel excited about this because you want to get to the lion cage and see those big cats close up. But your friend says that he is afraid to come because the lion might reach through the cage and get him. These are two different responses to the same situation. One of them is an example of catastrophising.

Ari makes a catastrophe out of not being able to spell “Theodore Street”. It links to his belief that his trouble with reading, writing and spelling means that he is stupid and he makes this an even bigger catastrophe by thinking his family will be angry about it. That means he can’t talk to anyone he trusts about his problems, and he has to find ways to hide them. This in turn leads to the situation with the boat, and nearly drowning: a real catastrophe.

Managing catastrophising requires a calm head. Using clear, logical thinking is one way. Testing the logic of thoughts by comparing them to other people’s experiences can be helpful. For instance: “Has anyone else I know ever been bitten by a lion at that park? What kind of precautions do they take to stop the lions getting people?” Or: “Do other people have trouble with spelling? Do my parents often get angry with me when I am having trouble with something?”

Dominant vs subjugated stories

As we experience events in our lives, we interpret them according to our own set of beliefs. The same event happening to two different people can be interpreted in opposite ways. One reason for this is that we have each internalised “stories” about ourselves that we fit our experiences into. For example, if we are used to being told and responded to as if we are an academic failure, a one-off experience of succeeding will be “subjugated” or minimised by our pre-dominant story (of being a failure) and interpreted as a fluke. Our dominant story will dominate when we interpret events. If we want to reinvent ourselves, or develop a new dominant story, we must pay attention to our subjugated stories – those which we dismiss easily because they do not fit into our current way of thinking about ourselves. An example of this could be: Sarah was always a little scared of using the telephone as she couldn’t see the reactions of the person she was speaking to. She called herself shy and developed a story about not wanting to upset people if she had to be direct in a conversation. This meant that she would get other people to make calls for her about difficult issues. It also meant that she found it difficult to face conflict in business situations. When she considered that this could be a dominant story that was making life difficult for her, she began to experiment with making phone calls herself. She decided she could experiment with being a “brave” person and someone who could discuss difficult issues well. This decision led to her making some phone calls that she wouldn’t have made before, and managing them. This in turn meant that she had some evidence for herself that she could manage difficult situations and she could make phone calls. Her dominant story was then challenged and changed.

Ari has a dominant story that influences him in many spheres of his life. He finds it difficult to see any other stories about himself as true.

Just thinking about this concept may encourage you to identify some of the dominant stories that you or people in your family live by. The key idea here is that we do not have to be defined by these things, we may challenge them and thereby change our story. They are simply ideas that have taken root and grown branches.

Avoidance

Avoidance is one of the major factors that feeds anxiety. Whenever we face something scary or something that makes us nervous, one of our choices is to walk away – to avoid it. This is like self-sabotage: it means that we don’t do the job interview, or make the new friend, all because of the scary feeling that we have on the inside. We let the fear take control. In order to get rid of the fear, we avoid the situation. The next time we come across a similar situation we are more likely to avoid it again, thereby developing a pattern of avoidance. Ari is caught in an avoidance trap. He is desperately trying to avoid his teacher and family finding out how difficult reading and writing is for him. This leads to all sorts of avoidance behaviours, and eventually to a life-threatening situation.

Identifying what we do when we are scared can mean that we give ourselves choices about how we behave in these situations. Avoidance is a choice, but there are other choices too. You might like to think about the times people in your family avoid things and examine whether avoidance has become a way to cope with the world. Beginning to face your fears with support will mean that they decrease in intensity.

As we experience events in our lives, we interpret them according to our own set of beliefs. The same event happening to two different people can be interpreted in opposite ways. One reason for this is that we have each internalised “stories” about ourselves that we fit our experiences into. For example, if we are used to being told and responded to as if we are an academic failure, a one-off experience of succeeding will be “subjugated” or minimised by our pre-dominant story (of being a failure) and interpreted as a fluke. Our dominant story will dominate when we interpret events. If we want to reinvent ourselves, or develop a new dominant story, we must pay attention to our subjugated stories – those which we dismiss easily because they do not fit into our current way of thinking about ourselves. An example of this could be: Sarah was always a little scared of using the telephone as she couldn’t see the reactions of the person she was speaking to. She called herself shy and developed a story about not wanting to upset people if she had to be direct in a conversation. This meant that she would get other people to make calls for her about difficult issues. It also meant that she found it difficult to face conflict in business situations. When she considered that this could be a dominant story that was making life difficult for her, she began to experiment with making phone calls herself. She decided she could experiment with being a “brave” person and someone who could discuss difficult issues well. This decision led to her making some phone calls that she wouldn’t have made before, and managing them. This in turn meant that she had some evidence for herself that she could manage difficult situations and she could make phone calls. Her dominant story was then challenged and changed.

Ari has a dominant story that influences him in many spheres of his life. He finds it difficult to see any other stories about himself as true.

Just thinking about this concept may encourage you to identify some of the dominant stories that you or people in your family live by. The key idea here is that we do not have to be defined by these things, we may challenge them and thereby change our story. They are simply ideas that have taken root and grown branches.

Avoidance

Avoidance is one of the major factors that feeds anxiety. Whenever we face something scary or something that makes us nervous, one of our choices is to walk away – to avoid it. This is like self-sabotage: it means that we don’t do the job interview, or make the new friend, all because of the scary feeling that we have on the inside. We let the fear take control. In order to get rid of the fear, we avoid the situation. The next time we come across a similar situation we are more likely to avoid it again, thereby developing a pattern of avoidance. Ari is caught in an avoidance trap. He is desperately trying to avoid his teacher and family finding out how difficult reading and writing is for him. This leads to all sorts of avoidance behaviours, and eventually to a life-threatening situation.

Identifying what we do when we are scared can mean that we give ourselves choices about how we behave in these situations. Avoidance is a choice, but there are other choices too. You might like to think about the times people in your family avoid things and examine whether avoidance has become a way to cope with the world. Beginning to face your fears with support will mean that they decrease in intensity.

Research Collaboration Opportunity For Canterbury Schools and Families

We need you to be a collaborator with us on the Rising Tide project.

As the book’s intention is to increase emotional resilience, Massey is going to research whether this actually happens. As a teacher or a parent collaborator, all you would need to do is go online and fill out a ‘baseline’ questionnaire about your class or child's behaviour now, and then after using the resource with your family or class, go back online and complete the survey again. We would hope to show a difference in behaviour due to the use of the resource.

This is a way for Cantabrians to contribute to disaster recovery research.With the many natural disasters that seem to be occurring in our nation, this research may inform how agencies and the government work with families and schools in future situations. Please sign up by emailing the research team (Benita Stiles-Smith) at [email protected]

We need you to be a collaborator with us on the Rising Tide project.

As the book’s intention is to increase emotional resilience, Massey is going to research whether this actually happens. As a teacher or a parent collaborator, all you would need to do is go online and fill out a ‘baseline’ questionnaire about your class or child's behaviour now, and then after using the resource with your family or class, go back online and complete the survey again. We would hope to show a difference in behaviour due to the use of the resource.

This is a way for Cantabrians to contribute to disaster recovery research.With the many natural disasters that seem to be occurring in our nation, this research may inform how agencies and the government work with families and schools in future situations. Please sign up by emailing the research team (Benita Stiles-Smith) at [email protected]